|

By Mark Montague, DAT Solutions

Less than 10 days after Hurricane Harvey made final landfall near Cameron, Louisiana, on Aug. 30, trucks were moving freight out of southeast Texas with almost the same volume as before the storm.

Houston's van freight volume rebounded to 88% of pre-storm levels during Labor Day week. Volumes have fallen since then; the plunge in volume leads me to believe there was pent-up demand to move freight as soon as roads would allow it but, in the weeks that followed, manufacturing production had yet to return to more normal levels.

Then came Hurricane Irma.

Like Harvey, Irma's toll on human life was brutal and the storm upended freight transportation systems in the Southeast and other parts of the country. But Harvey and Irma are both unique and offer a number of distinct lessons for anyone who moves freight.

Big Weather Event or Something More?

The hurricanes' impact on freight appears to be following patterns that are typical of a "big weather event" like Super Storm Sandy in 2012 and Hurricane Katrina in 2005. These tend to affect freight movements in three stages:

1. Before the storm: Unlike an earthquake or other unpredictable events, a storm can be forecasted well in advance, giving shippers time to plan and react. Outbound rates may increase sharply, but goods can be rerouted, stockpiled, and potentially saved from spoilage. FEMA and other organizations may stage emergency relief supplies on the outskirts of the storm zone so they are ready to act as soon as roads are clear.

2. During the storm: Nothing moves in or out of the area until conditions are safe. Restoring service and schedules depends on the availability of commercial power and the condition of roads, rails, ports, and other infrastructure.

3. After the storm: In terms of freight, emergency supplies tend to be brought in first, followed by van and reefer freight. Flatbed demand picks up when it's time to bring in construction equipment and materials for cleanup and rebuilding.

Accepting loads into a storm-affected area can be a difficult choice for a carrier. On one hand, an inbound load can represent an opportunity for additional revenue—inbound rates tend to shoot up after a big weather event. However, a truck might have to wait an extended period of time to get unloaded, which raises questions about the availability of fuel and essential services for the driver, and the lack of outbound freight means the trucker may need to deadhead out of the region.

|

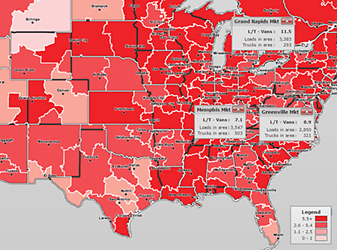

Click here to view larger. This DAT Hot Market Map shows load-to-truck ratios in markets across the Midwest and South on Aug. 30, the day Harvey made its final landfall. As trucks rushed to move relief supplies into Texas, they left a void up north in places like Grand Rapids, Mich., with a load-to-truck ratio of 11.5.

Click here to view larger. This DAT Hot Market Map shows load-to-truck ratios in markets across the Midwest and South on Aug. 30, the day Harvey made its final landfall. As trucks rushed to move relief supplies into Texas, they left a void up north in places like Grand Rapids, Mich., with a load-to-truck ratio of 11.5.

Houston's Size and Scope

One thing that distinguishes Hurricane Harvey from Irma is the significance of Houston to the national economy.

Houston is home to a number industries including energy exploration and refineries. It's a major hub for rail and marine freight. In trucking, it's the No. 1 source of flatbed loads and one of the top five or six markets for van and refrigerated freight.

Distribution centers near Houston serve at least six states. After Harvey, some shippers began to supply markets ordinarily served by Houston from regional hubs in the Southeast, including Atlanta, Charlotte, and Memphis. Warehouses in the Midwest were called on to supply the Northeast in order to compensate for freight that otherwise would have come from Atlanta. Many of those warehouses had to supply Colorado and other out-of-the-way markets served by Houston.

I think it's telling that on Aug. 30 the worst truck shortage was in Grand Rapids, Michigan. Trucks were being diverted to deliver emergency relief to staging areas in markets like San Antonio and Dallas, leaving shippers in the Midwest scrambling to move seasonal freight, including apples and potatoes, as well as the usual consumer goods.

The storms tested the resiliency of supply chains but also showed what a resourceful group of professionals we have in the industry. Many offered equipment, warehousing, and other resources to organizations like the American Logistics Aid Network. You never know when the next big event is coming, and your help would be greatly appreciated.

Mark Montague is industry rate analyst for DAT Solutions, which operates the DAT® network of load boards and RateView rate-analysis tool. He has applied his expertise to logistics, rates, and routing for more than 30 years. Mark is based in Portland, Ore. For information, visit www.dat.com.

|